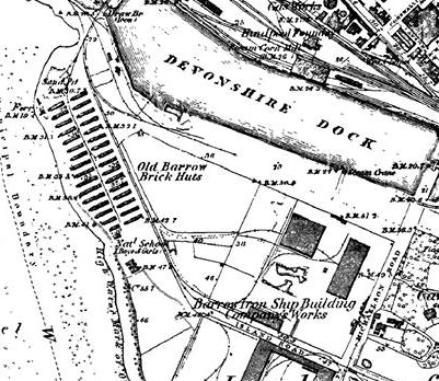

1870 witnessed the forming of Ramsden and Devonshire’s brain-child, the Barrow Iron Ship Company with capital of £1,000,000. In

1871 work began on the monster that was to eventually dominate the island. Two years later in 1873 it occupied fifty five acres: but that

was only the beginning.

Work started in January 1871 but a gale of hurricane force severely damaged the newly constructed buildings, nevertheless building

went on apace and when the yard, planned by Scottish Shipbuilder Robert Duncan, was only partially completed it employed 600 men. At

this point one of infant Barrow’s major, and on-going problems was housing.

Already a disgrace even by Victorian standards, the situation was

exacerbated by the new shipyard’s demands for labour. The ore mines and

iron works attracted thousands of navvies and miners from all over the

country. Contractors from far and wide worked on Devonshire and

Buccleuch Docks. Barrow’s housing capacity at that time was simply

unable to cope with the extra influx of labour, bringing with them in some

cases their families as well. The frontier town aspect of Barrow in the rip-

roaring 1860’s has been well documented. Ramsden and Devonshire, well

aware of the accommodation problem, nonetheless ploughed ahead with

their project for an iron-ship building yard on Barrow Island. Only later,

when the town and Barrow Island were full to bursting point, did they

make a effort to decently house the vast numbers of workers employed in

their various schemes. One of the more unsavoury sights thrown up by

need to at least, put a roof over the heads of the workforce, were the

Barrow Island Huts.

The first Huts were built of wood, the later ones brick. They were

erected [for want of a better word], along the shore from the [later], Ferry

Beach, to where until recently VSEL slipways were laid out. Later other

“cottages” were built on land where Devonshire Buildings now stand.

Insanitary is a word that does not adequately describe the conditions the

inhabitants of the Huts tolerated; squalid hovels is a glowing description of

the buildings themselves. While the shipyard’s upper management enjoyed

the salubrious delights of the newly built Cavendish Park Villas, the

unskilled labour suffered in conditions slightly better than living in a cave.

“DAMNABLE DENS.” In 1875 “The Vulcan,” another newspaper of the

day, denounced the conditions men in the steelworks were suffering at a time

of reduced wages and increased hours. Using the Huts as an example of the

worst environment imaginable, the editor extended sympathy to the...”Wives

and families huddled together in overcrowded purlieus, or in abominable and

damnable dens like those on Old Barrow.”

The wooden Huts, even by Victorian standards were so gruesome that

they were condemned in 1877. The Brick Huts however, built in three distinct

blocks: known as “40”,”60” and “80” blocks, remained in place for almost

another ten years. An inhabitant of the Huts in the early 1870’s was a

seventeen year old girl whose father came to Barrow with his wife and family

looking for work. They found that far from the streets being paved with gold -

they were “paved” with mud, raw sewage and recently deceased animals. Forty

five years later, in a letter to the now defunct Barrow News, the girl described

in vivid detail... “Life in the Huts,”

The girl lived at No 13, “40 Huts” the oldest block of the three. These

were built of brick on the outside, with thinly plastered internal walls. The only

water available was from a stand-pipe in the middle of the block; drainage was

non-existent & oil lamps provided lighting. One toilet per eighty persons was

yet another admirable feature of Hut life. Admirable of course, unless you

happened to be number seventy nine in the queue with dysentery. When

Smallpox struck the area the hospital would only admit working men, the

women & children had to fend for themselves the best they could. A certain Dr? Grieves ran the hospital with the help of a one-eyed Crimea

veteran, himself a lodger in the Huts. They did what they could for the victims, but as soon as they were beyond human help they were

buried the same day. Spiritual help was equally scarce. The girl in a letter noted, “Never once seeing a Minister of the Gospel in the Huts.”

Finally to everyone’s relief the “40 Huts burnt down.

An impression of the type of character who lived in the Huts can be gleaned from their favourite decor - the walls of some Huts were

gaily adorned with pictures of boxers & murderers of the day. The Hutkeeper, the man in charge of allocating lodgings to newcomers &

general caretaking had a side line; selling beer! Far from keeping order in this unruly settlement, he added to the mayhem by

indiscriminately selling liquor to the worst trouble-makers & malcontents. The few policemen Barrow had in those days usually gave the

Huts a wide berth. When forced to put in an appearance at a particularly nasty affray they made sure they went in mob-handed.

POETRY CORNER The Vulcan & the Barrow Pilot, another Barrow news-sheet, were instrumental in getting the wooden Huts

condemned. During a campaign to rid the town of them & their ilk, a poem was published. Witty but bitter. Heavily ironic although spirited.

It captures the free frontier-town grit these people possessed, entitled….

My Cottage by the Sea.

Upon Old Barrow’s sacred isle

O’er looking Piel’s historic pile,

Sir James and Co., have built for me

A little cottage by the sea.

In this home, sweet home, I dwell,

With wife and bairns and mates as well,

For lots of lodgers, lodge with me

In my cottage by the sea.

Not Darkies in a slave dhow hold,

Together huddled from the cold,

Are half of snug at night as we

In our cottage by the sea.

What though we’re somewhat closely pent

Yet lodgers more than pay the rent;

And add much to the jollity

Of my cottage by the sea.

For merry is the life we lead,

Here from every custom freed;

That would spoil the liberty

Of my cottage by the sea.

Inspector Barker doesn’t know,

How the whole hog we go,

Inspite of Mr Fell J.P.,

In my cottage by the sea.

The Bobby looks in now and then,

But, off he quickly slopes again,

Lest rough handled he may be

In my cottage by the sea.

And what care I, if once a year,

I’m fined five pounds for selling beer,

A licence cheaper could not be,

For my cottage by the sea.

Thus, I am able to despise,

The Police and Excise;

And with my mates get on the spree

In my cottage by the sea.

Bad for the youngsters! do they say?

But, let me train them my own way;

I’ll warrant then they’ll happy be,

In my cottage by the sea.

Some think the place in which I dwell,

Is a sort of little hell;

But my Masters built for me

My little cottage by the sea.

And to their credit it redounds,

That the kennels for their hounds,

Should more habitable be

Than my cottage by the sea.

Part of Joel Whitaker’s: “Barrow, An Eclogue, if not so witty,” is far more biting.

Contiguous, a constant mark for scorn,

The Muse, disgusted, views the Barrow huts:

A group of dens of aspect most forlorn,

Where half clad children tumble in the ruts

On which each ugly gable-end abuts,

While pigs and poultry wallow on the floor!

These filthy homes of even filthier sluts

By hundreds stand on Barrow Island’s shore,

A monument of sordid shame for ever more.

Whitaker may not have been able to hold a candle to Shakespeare, but he certainly made a vicious point. However for literary GBH,

with the subtlety of a sock full of marbles, the footnote to pages 48-49 gets the gold star…..

Ten shillings a week and £5 key deposit was a normal arrangement and on leaving the house the author of this invective considered:-

“The tenant may deem himself a spoiled child of fortune if the ‘damages’ do not amount to more than the sum he deposited.”

He continued,

How very little, since things were made,

Things have altered in the building trade.

“A Truthful Song” - Rudyard Kipling.

“DEVONSHIRE DENS” Mainly vanity caused vast new docks, buildings, large tracts of water and landmarks to be named after the

local notables, but it’s strange how their graces would not deign to have their names associated with “The Huts. “The names “Cavendish

Cabins” or “Devonshire Dens,” roll off the tongue quite nicely.

Walking through the front door of the average Hut brought a visitor into the “living room” with the only permanent furniture, a food

cupboard. There were no internal walls as such, just thin plywood partitions seven feet tall separating the bedrooms from the living room.

The plywood in places was split, so the girl had to stuff the cracks with newspaper, as she modestly put it, “To keep out the light.” Maybe the

prying eyes of the many lodgers and cold draughts were more of a problem than the light. In their particular Hut the girl’s father was quite

strict, only allowing four lodgers at any one time. Considering sixteen to eighteen people shared most Huts, the girl’s Hut was positively

underpopulated. The “40 Huts” were held to be the worst of the three brick built blocks, and just to make life a little more interesting, soon

after the were cosily ensconced in this Spartan ghetto, smallpox broke out, rapidly followed by a diphtheria epidemic. All this for only three

shillings, [15p], a week rent. However in 1874, when the company found out how much fun the inmates were having raised the rent to

3/6d. The mere £2,278 per annum clear profit from the lower rents was obviously giving the directors insomnia.

“DIRTY DENS” The residents believed the smallpox epidemic was carried by a Russian ship berthed by the “Black Huts”, [near the

site of the old “Cradle Bridge”]. Strangely, the disease only affected the “40 Huts”. Although all three groups of Huts were close together, it

didn’t spread to the “60” or “80 Huts.” The residents believed this was because the “40 Huts” were built in a depression in the ground and

the germs were so sick with the smallpox - they could crawl downhill to the 40’s, but didn’t have the strength to get back out again!

By the 1880’s conditions had improved slightly. The wooden huts had gone, the marginally better brick huts remained, but not for

much longer. The more enterprising had turned their hand to shop-keeping. According to the 1882 Furness and Cartmel Directory no less

than twelve individuals are recorded as having some sort of business in the Huts.

Built on the site of Devonshire Buildings, Shipyard Cottages although only temporary dwellings, were tolerable compared with the huts,

if only because they at least didn’t suffer the sheer, stifling concentration of numbers that was the Hut-dweller’s lot. They were erected in

seven rows to house the local Shipyard workers. As early as 1871 small business was establishing itself, Edward Lord had a shop at

numbers 11 & 12; George Collins at number 22; William Hastings at number 31 and James McGuire had a grocers at number 61.

Shipyard cottages were demolished in 1873 to make way for the Duke of Devonshire’s pet project Devonshire Buildings. Obviously

he didn’t have any toys as a child.

As early as 1866 Joseph Richardson writing as “Erimus” in the Barrow Times stated, “No accommodation could be had, under 5/- or

6/- [30pmax] a week, when a reasonable figure was considered to be 3/6d or 4/-.” [20p max]. The official population density figure for

Barrow in 1866 was 6 people per house, Richardson however, knew of twenty people living in one house - six to a room. Then, just when

things couldn’t get any worse; they did. Even the official figures rose.

1871....6.7 people per house.

1874....7.3 people per house.

The Barrow Pilot reported an angry meeting of hut-dwellers in 1874, who were trying to bring their plight to the attention of the Local

Government Board. Mr J. Wilson proposed a resolution calling for action by the Health Committee to improve sanitation, “Before some

pestilential epidemic breaks out.” [In this fervent wish he was a little late, as Typhus, Smallpox and Diphtheria had already swept through

the Huts]. A Mr Gough seconded the motion and remarked that, “The Corporation had the power to borrow [money] to build cottages. In

fact he’d heard they’d already borrowed £10,000 for that purpose.” He wanted to know where those cottages were [because]; “They were

not on Old Barrow!”

The chairman, far from keeping the proceedings in order, nearly caused a riot when he told the seething mob, about an extract from

the “Barrow Daily Times” which said the people of Old Barrow,

”Were not worthy of the sympathy of the rate-payers, as they were only a drunken lot of working men!”

It cannot be left unsaid - without those drunken working men, fat profits could not have been made by men in suits.

Conditions in those not so far off days were obviously far worse than anything today’s working man has to suffer. Having said that, not

a lot else has changed.

The men, and their forebears, who built Barrow’s docks were in all probability, the same type of men who worked under Isambard

Kingdom Brunel, Thomas Telford, George Stevenson et al; building bridges, tunnels, canals & railways. Barrow was only a stopping off point

on a long journey: to who knew where next?

RENT A DUMP. In the late 20th century, a latter day version of the itinerant contractor wanders this country, me included. By and

large, much the same group of men that worked on Heysham Power Stations could be found on the Rampside Gas Terminal and worked on

the construction of THORP at Sellafield also the DDH at Barrow. They will now drift to the next big job, wherever it may be. They will take

what lodgings they can find, handy for the job, and at this point Joel Whitaker’s “Robber” and the “Robbed” come into contact. Some

unscrupulous landlords - eager to turn a fast buck; cram as many bodies as possible into an overpriced broom cupboard, happy in the

knowledge theirs are the only “digs” for miles around.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la meme chose!

“With a few exceptions, owners of house property in Barrow are spoken of with a degree of bitterness and

hatred that only cruelty and oppression can arouse in the breast of a free people. Highway robbery, pocket-

picking, keeping a sea-side lodging house, garrotting and burglary are gentle charity and active benevolence

compared to the operation of Barrow property owners. I am in a position to fix dates, specify houses and give

the names of landlords and tenants who even a Shylock would have been ashamed.”

“Bear in mind that the rent has been paid in advance; and that the agreement between the Robber

and the Robbed, is for the occupancy of a structure from which a well-bred dog, accustomed to the

elegances and refinements of a kennel, would scamper howling ....and these men have the audacity to

seek, and when obtained, to occupy, seats in the Council Chamber.”

What is the plural of Hut? Hutch?